You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Feminism’ category.

Back in September, when the alleged-then-retracted Hofstra gang rape was front page news, I made the following observations about it:

If a woman is raped by a man she’s been intimate with before, or raped in the course of a sexual encounter that began as consensual, or raped in circumstances in which her judgment may be called into question, she can expect to be disbelieved, shamed, and attacked, and that expectation may lead a rape survivor to alter her story to make it more palatable to police, or to a jury, or even to her friends and family.

I don’t know what happened that night, and I expect that I never will. I’m not accusing any of the five men who were named of anything, and I’m not saying that the fact that they were accused means they must have done something wrong. I don’t know, and I’m not interested in speculating.

I do, though, want to say clearly that the question of what happened isn’t a binary one of “she told the truth, and they’re guilty” vs. “she lied, so they’re innocent.”

It’s possible that she lied and that some or all of them are guilty.

Yesterday the historian KC Johnson stumbled across that post, and concluded from it — I swear I’m not kidding — that I’m a “campus ideologue … trained to believe that women never lie about rape.”

We know for a fact that Danmell Ndonye lied about rape, because she told two contradictory stories about an alleged rape. My entire post was premised on the obvious fact that women sometimes lie about rape. In a comment on that post — a comment Johnson quoted from — I said that Ndonye’s “allegation should not have been taken as proof that she was the victim of a sexual assault.”

But apparently I believe that women never lie about rape.

And that willful misreading isn’t enough for Johnson. He goes on to pull the last sentence of my post out of context, snip away the crucial italics, and offer it as my “startling claim” that “it’s possible that [Ndonye] lied and that some or all of them [the falsely accused men] are guilty.”

As I said in a (long trapped in moderation purgatory) comment at Minding the Campus, the Manhattan Institute blog where Johnson’s post appeared, there are two factual claims in my blockquoted passage above: first, that “a rape survivor [may] alter her story to make it more palatable to police, or to a jury, or even to her friends and family,” and second, that it was possible — not likely, not probable, just possible — that Ndonye’s original lie was a lie of that kind.

Johnson finds these suggestions preposterous.

And I find that deeply depressing.

Postscript: Four days after my original post on the Hofstra case, the Nassau County DA decided that she would bring no criminal charges against Ndonye. Under the terms of an agreement between Ndonye and the DA’s office, Ndonye stipulated that she had not been sexually assaulted or sexually abused by the men she had accused. The DA was later quoted as saying that she was convinced that what happened that night was consensual, and I have no reason to doubt her assessment.

October 14 update: It took two Twitter messages, an email, and a week’s wait, but the folks at Minding the Campus have finally posted the comment referenced in this post, as well as a link to this post.

Dr. Terence Kealey, a top administrator at a major British university, is facing a torrent of criticism for writing that staring at female students in class is a “perk” of teaching college.

Dr. Terence Kealey, a top administrator at a major British university, is facing a torrent of criticism for writing that staring at female students in class is a “perk” of teaching college.

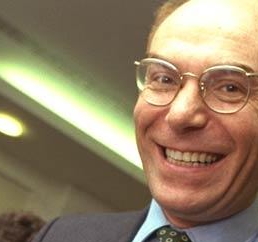

In the same article — a humor piece for the Times Higher Education supplement — Kealey (pictured at right) called the idea that student-faculty sex “represents an abuse of power” a “myth.”

He also compared classrooms to high-end strip clubs.

Olivia Bailey, the Women’s Officer of Britain’s National Union of Students, said she was appalled by Kealey’s “astounding lack of respect for women,” and commenters online have called the article a defense of sexual harrassment.

But Kealey, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Buckingham, is unrepentant, saying he was merely ” employing humour to highlight the ways by which people try to resolve the dissonance between what is publicly expected of them and how they actually feel.”

I came across a blogpost this morning (via @HappyFeminist‘s Twitter feed) that asked what struck me as an interesting question, and I’d like to take a swing at answering it:

How do you teach feminism if you are not a feminist?

To answer this question, it seems to me, the first thing you need to do is to define your terms. If by “teaching feminism” you mean teaching about feminism as a movement, then you teach feminism the same way you teach Marxism, or existentialism, or surrealism — with as full and as sympathetic an understanding of the movement (and of its critics) as you can muster. If you’re going to talk about feminism in the classroom, you have an obligation to learn enough about it to talk about it intelligently, and that’s an obligation you have whether you’re a feminist or not.

In her post, Ashley says some teachers don’t teach feminism because they think they don’t know enough about it, or because they haven’t thought about teaching it, or because they don’t have time. She’s right, but those objections shift the topic a bit — from how you teach feminism to when.

So when should you teach feminism? When it’s part of the story you’re trying to tell, and when it’s part of the toolkit you’re trying to help your students assemble. More broadly, you teach about gender when it’s relevant … and when you’re talking about people, gender is almost always relevant.

You don’t need to “teach feminism” to talk about gender, of course, and you don’t need to teach from a feminist perspective to talk about gender. You do, though, need to have an understanding of how gender works. You need to have an analysis of gender, a perspective on gender. (More to the point, you need to have a considered perspective on gender, because by the time you can talk you have a perspective on gender, whether you realize it or not.) You need to know how you’re going to come at gender issues when they arise, you need to know why you’re taking the approach you’ve chosen, and you need to know how you’re going to work productively with students who are coming from a different perspective.

And of course that last paragraph applies as much to activists as it does to teachers.

October 7 update: Readers coming from Minding the Campus should know that I take issue with KC Johnson’s gloss on this post. I’ve submitted a comment to that effect over there, and written a follow-up post here as well.

In a new post this morning about last week’s Hofstra rape case — in which a student initially said she’d been raped by five men, then withdrew her allegations — Jaclyn Friedman writes the following:

There’s a widespread assumption that recanting an accusation means that you’re admitting you lied. But in reality, lots of victims recant not because they made it up, but because they come to the unfortunate realization that it will cost them more, emotionally, to pursue justice than to let it go.

We’ll probably never now what happened in this case, but it’s entirely possible that she was threatened by the accused perpetrators or their associates, interrogated by the police about her sexual history or what she might have done to “provoke” the attack, or blamed and slandered by the media or people in her community. All of these things happen all too often to rape victims who speak out. Let’s not ignore the possibility that they happened here.

This is important stuff to keep in mind, and Friedman makes other good points along the way. But I’d like to take it a step further: Even if the Hofstra student lied in her original statement to the police, it doesn’t automatically follow that she wasn’t raped.

The cultural pressures that lead women to falsely recant rape charges are the same pressures that lead women to blame themselves, or expect blame from others, when their rapes don’t follow an accepted narrative. If a woman is raped by a man she’s been intimate with before, or raped in the course of a sexual encounter that began as consensual, or raped in circumstances in which her judgment may be called into question, she can expect to be disbelieved, shamed, and attacked, and that expectation may lead a rape survivor to alter her story to make it more palatable to police, or to a jury, or even to her friends and family.

I don’t know what happened that night, and I expect that I never will. I’m not accusing any of the five men who were named of anything, and I’m not saying that the fact that they were accused means they must have done something wrong. I don’t know, and I’m not interested in speculating.

I do, though, want to say clearly that the question of what happened isn’t a binary one of “she told the truth, and they’re guilty” vs. “she lied, so they’re innocent.”

It’s possible that she lied and that some or all of them are guilty.

A tongue-in-cheek call for a campus club to “advocate for men in the same manner that female groups advocate for women” has resulted in the formation of a men’s advocacy organization at the University of Chicago.

Back in March, UC junior Steve Saltarelli wrote an op-ed in the Chicago Maroon announcing the creation of Men in Power, a new student group founded “to spread awareness and promote understanding of issues and challenges facing men today.” Proposing “a tutorial on barbecuing” and “fishing, hunting, and flag-football retreats” as club activities, Saltarelli soon started receiving emails from men looking to join.

So he set it up. MiP applied for official campus recognition and funding, and held its first meeting in mid-May.

The Chicago Tribune had no trouble finding men’s rights activists to cheer the group’s creation and feminists to deplore it, but it remains unclear just how serious Saltarelli is. His Maroon op-ed was an obvious spoof — “many don’t realize that men are in power all around us,” he noted, pointing out that “the last 44 presidents have been men.” But if the club itself is a hoax, it’s a subtle one, as interviews like this one make clear.

That said, the club is clearly uncomfortable with the charges of misogyny (and douchebaggery) that are directed its way. Its Facebook group and website each include a prominent notice that those “looking for a (white) male champion group that seeks to advance men at the expense of women and/or a clique to isolate yourselves … are in the wrong place.”

Links posted at the group’s Twitter feed make clear that it’s garnering quite a bit of media attention, but its first meeting drew fewer than twenty attendees. If it exists as a functioning campus group a year from now, I’ll be more than a little surprised.

Update: Okay, here’s my hunch. Saltarelli wrote the original Maroon piece as a not-feminist-but-not-antifeminist-either goof. He wasn’t serious about creating the group. But then he started getting attention, and he liked the attention, so he decided to go for it. And then he started getting a lot of attention, and a lot of questions he’d never really contemplated, and he had to start figuring out how to answer them. And now he, and the rest of the group, are trying to come up with a serious rationale for a project that didn’t start out serious, and negotiating some heavy gender politics that they don’t have a lot of tools to address.

(There are a lot of parallels here to the Veterans of Future Wars craze of 1936. I should really get some of the stuff I’ve written about those folks up online.)

Recent Comments