You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Students’ category.

As Donald Trump inches closer to the Republican presidential nomination, protests at his speeches are heating up. And with those protests comes hand-wringing about whether the activists targeting Trump are helping him more than they hurt him.

It’s a hard question to answer. Trump has certainly become more popular with Republican primary voters in recent weeks, but he’s also become less popular with the electorate as a whole, so it’s possible that anti-Trump demonstrations may be giving him a boost him in the primaries while damaging him for the general election. It’s also possible that how public opinion on these protests shakes out depends on how they develop — if a protester is badly injured by Trump supporters, say, that could change public perception quickly.

The bottom line is that we just don’t know how these actions are shaping public opinion. We have guesses, but we don’t have data. And in the absence of data, we tend to fall back on analogies and historical precedents.

One such appeal to history came this afternoon from Jonathan Chait, who tweeted that

civil rights protestors had rigorous criteria for justifying civil disobedience. They didn’t try to shut down Goldwater.

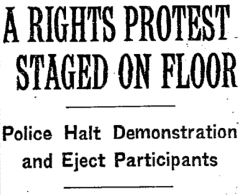

I was curious as to whether this was true, so I did what Chait clearly had not — I googled it. More precisely, I did a search of the New York Times’ archives for 1964 on the terms “Goldwater” and “protest.” And it turned up this:

That’s a July 16, 1964 Times article about a demonstration at the Republican National Convention in which twenty civil rights activists were ejected from the floor for disrupting the proceedings in protest of Barry Goldwater’s nomination for president.

And if you read the whole article, you’ll see that the activists, who were members of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), a major civil rights organization, used tactics that were essentially identical to those used by Trump’s critics today. They smuggled in a banner. They linked arms. They chanted. They went limp when arrested.

And Barry Goldwater went on to defeat in one of the biggest landslides in American political history.

The Goldwater protest wasn’t unique, either. After I tweeted it, others quickly provided similar cites — of LBJ supporters jeering Goldwater at a Toledo campaign stop in 1964, and of student activists heckling George Wallace in 1968. The Wallace incident has additional resonance with today, too: According to the newspaper’s account, Wallace supporters assaulted protesters before the candidate even arrived, Wallace himself taunted the activists at the start of his speech, and several protesters were beaten further as they were dragged handcuffed from the venue.

And how did those campaigns work out? Well, like I say, Goldwater was defeated in one of the most devastating landslides in American political history. Wallace steadily declined in the polls as the campaign wore on, failing in his goal of throwing the race to the House of Representatives in order to establish himself as a force to be reckoned with in negotiations over the presidency.

Does this mean that the Trump protests are destined to have a positive effect, or even that the Goldwater and Wallace protests were a good idea? No. But it does serve as a reminder that our memories of past social movements are woefully limited, and that it’s always a bad idea to judge today’s activists by the standards of an invented, sanitized past.

Update | For more on this kind of historical amnesia, see this post from last November, in which I discussed some ways in which criticism of today’s student organizers echoes the rhetoric that was used to attack the civil rights activists of the 1950s.

This is the first part of a three-part essay comparing USNSA in 1966 with its successor, the United States Student Association, fifty years later. The second installment is here.

• • •

For most of its first two decades, the United States National Student Association (USNSA) was a liberal, but cautious, force in American student organizing.

Founded in 1947, USNSA was a federation of student governments with hundreds of member campuses around the country. It had taken progressive stances on issues like civil rights and student power from its founding, but it was always aware of its limits — because its base was in student government, it could never get too far ahead of student opinion on the campus.

Over the course of the early 1960s, USNSA’s activists grew increasingly discouraged. The organizing victories of the lunch-counter sit-ins, the Freedom Rides, and the campaign against nuclear testing hadn’t created a broad, sustained movement presence on the campuses, and many of those who had been pushing for student empowerment on the campuses eventually burned out, graduated, or both.

By mid-1964, though, it had begun to seem like all the previous years’ work was beginning to bear fruit. Freedom Summer led to the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, and with the escalation of the war in Vietnam in the spring of 1965, antiwar protest escalated too.

USNSA’s summer 1965 National Student Congress, reflected this transformation only dimly. In an article in that Congress’s mimeographed conference newspaper, Hendrik Hertzberg (then a student journalist, now of the New Yorker) described that Congress as “in some indefinable way hipper, more aware that life does not begin and end with resolutions and caucuses, than the one that preceded it.” But “hipper” is not the same as “hip” — that Congress’s biggest speech was given by Vice President Humphrey, and the convention closed with the singing of “We Shall Overcome” and the national anthem. Activists made their presence known in 1965, and they pushed for change in the Association, but they didn’t transform the space, and tellingly participation in that Congress was among the lowest in USNSA history.

During the year that followed, three USNSA staffers drafted lengthy reports on the status and prospects of the Association, and although each approached the problem from a different perspective, all arrived at the same fundamental conclusion — that the Association would grow only if it strengthened its ties to the American campus and embraced a more aggressive direct action agenda.

Such projects were already beginning to appear by then. The Association sponsored a “Freedom Christmas” voter registration project in the South at the end of 1965, for instance, and developed a program of assistance to American anti-apartheid protesters. But the most significant transformations of 1965-66 came in NSA’s relationship to its members. The Association mounted regional conferences throughout the country that year, and mandated that members of its board of directors conduct campus visits in their regions. (After losing three close affiliation referendum battles in the fall, NSA won all seven referenda that were held in the spring.)

And if change was growing visible within USNSA, it was now impossible to miss on the campus. In the wake of Berkeley and the Vietnam escalation, student activism became a cultural and media phenomenon across the United States. At the very moment when campus activists had given up on organizing students, they discovered that students were beginning to organize themselves.

This change was perhaps most obvious in the student government elections of the spring of 1966. As students came to see themselves as activists, they gravitated to activist candidates for student government office. Again and again that spring, activists who had run for student government as protest candidates — to get a voice in debates, or coverage in the student newspaper, or just a space to express their views — found themselves winning.

The 1966-67 president of the Stanford student government, David Harris, was a perfect example. A leader in campus protests, he had been approached by a leader of the small activist faction in the campus student assembly to run as a protest candidate for student government president. He would lose, he was told, but in running he would have a platform from which to publicize an activist agenda.

Fraternities had long dominated the Stanford student government, and Harris stood out among his fellow candidates that year. While he strolled the campus in jeans and what the campus newspaper called a “beatnik-style” haircut, the others campaigned in suits and ties. He ran on a platform that he described later as:

“Elimination of the Board of Trustees, student control of student regulations, equal policies for men and women, the option to take classes on a pass-or-fail basis, legalization of marijuana, and the end of all university co-operation with the conduct of the War in Vietnam.”

Harris was a sensation. He led the field in the first round of voting, and a week later beat a fraternity candidate in the runoff, an election that saw the highest turnout in Stanford history.

At the NSA Congress that summer Harris emerged as one of the strongest radical voices in the Association, and soon he would be a movement celebrity — co-founder of the draft-resistance group The Resistance, subject of an Esquire feature on “The New Student President,” and husband of folksinger Joan Baez, whom he met while both were jailed for their participation in a draft protest.

This was the context for the 1966 National Student Congress: USNSA’s twentieth annual summer convention.

The Vassar College administration has threatened to pull all funding — nearly a million dollars — from the Vassar Student association (VSA) over a proposal to join a boycott of Israel.

The threat came in a meeting with student government last week, and was reiterated in a joint letter from Vassar president Catharine Bond Hill and dean Chris Roellke, in which the administrators said that the college could respond to such a boycott by “vetoing the proposal … taking away the VSA’s authority over spending the activities fee, or overseeing that spending in some way so as to prevent it from implementing the boycott.”

In the statement, Hill and Roellke said that while “VSA has the right to endorse the BDS [Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions] proposal, given our commitment to free speech,” that right did not extend to an actual boycott. “The college,” they wrote, “cannot use its resources in support of a boycott of companies.”

It’s hard to make any sense of this distinction. Surely an endorsement of a boycott is a use of resources in support of that boycott, if anything is. Joining a boycott, on the other hand, is by definition not a use of resources — in fact, it’s the opposite.

For now, though, this distinction is moot. While VSA endorsed BDS by a 15-7 vote at its meeting this Sunday, they declined to join the proposed boycott themselves. (The vote on that proposal was 12 in favor to 10 against, but it required a two-thirds majority for passage.)

But while the VSA vote saves them from the prospect of defunding by Vassar, the threat itself should give us pause. Student control of student money is a core principle of shared governance, and the threat to snatch such control away over a boycott of Ben and Jerry’s is an indication of either incredible hubris or incredible nervousness — or both.

The Vassar administration’s threat was preposterously stupid, in other words. And I expect we’ll be seeing more like it as the student movement continues to ramp up.

My grandmother was born a hundred years ago today. Here’s something I wrote when she died ten years ago.

I didn’t know my grandmother very well.

She lived in Northern England, and I only saw her perhaps every three years — fewer than a dozen times, maybe, in my life.

I didn’t know my father’s parents very well either, but they were a bit easier to know. They were Americans. They were secular. Tessie was English and Catholic. Very Catholic. My mother was the oldest of seven.

Tessie’s oldest child, born during the war in the summer of 1941, got her nursing degree and went swanning around Europe and the Middle East — a good girl cadging rides on the back of young men’s motorcycles. After the Middle East it was on to America, where she found a nursing job in New York and reconnected with the good boy from Idaho that she’d met in Rome.

By 1967 my mom was the first of Tessie’s kids to marry. The service was in a Catholic church, but my mother and the priest were the only Catholics there. No family on either side could afford to make the trip. My dad — memory tells me — bought a tie and borrowed a suit. The wedding cake was from Carvel.

My grandfather died a few months after that, of a heart attack. He smoked. He was in his fifties. Several of the kids were still at home, the youngest just five years old.

When my mom came back to visit, she was a hippie, or so it must have seemed to Tessie. She raised three American children, smart and wild and uncouth.

I had no idea what Tessie expected of me. My parents talked to me as if I was an adult, and I talked to Tessie the same way. Tessie chastised me, and my mother chastised her.

When I was about five Tessie married Steve Lesnowski, and took his name. She had been born a Hartley, and married a Gittins. Her daughters were by then marrying Johnstons and Garveys and Brays. To my young eyes, Teresa and Steve Lesnowski were the most English of them all.

(Later, I would have their Englishness and their humanity confirmed by Billy Bragg, whose paean to young clumsy romance had a chorus — Adam and Eve are finding out all about love — that swapped out the Biblical names for “Teresa and Steve” the last time through.)

Steve was a good man. Good and funny and quiet. He loved Tessie and treated her well. John, the great love of her life and the father of her seven children, loomed large, it seemed to me, but I didn’t know much.

Tessie was sometimes hard to be around when I was a kid. She seemed constantly tetchy and often angry. She seemed to always disapprove, even when I thought I was being good.

But then… I won’t say here what it seemed the turning point was, because I’m not sure I’m right and I don’t want to say it and be wrong. But then. She relaxed. She calmed. She seemed to inhabit her position as matriarch of her great clan with an ease she’d never found before. At seventy she was difficult, but at eighty I looked forward to seeing her.

We chatted, in the last few years. About Casey, and about young Angus, and about her clashes with young Angus’s mom. About my father. About nothing at all.

As I grew to like her, I saw more of my mother in her, and that was a gift.

• • •

A few weeks ago, my mother told me today, Tessie fainted. When she was revived, she said she’d heard voices, and maybe seen lights. She felt like — in my mom’s quote or paraphrase — she was “being carried on a cloud of cotton wool.” She believed she was being taken to the cemetery where her husbands were waiting for her. She was, my mom thinks, a little disappointed to be brought back.

And then on Monday morning she didn’t come back.

I’ll miss her.

Last night on Twitter it was claimed that Bernie Sanders supporters at a Nevada caucus shouted down activist icon Dolores Huerta with chants of “English Only!” when she tried to serve as a translator for Spanish-speaking caucus participants.

The claim shocked many, and circulated widely, but others at the caucus stepped forward to say that it wasn’t true. Eventually, full video of the caucus emerged, and it backed up the Sanders supporters — there’s no evidence of an “English Only!” chant on the tape.

I’ve watched the video several times. Here’s what happened:

At about 51:45, the chair of the meeting, a neutral party, starts explaining the caucus procedures — speaking quickly, and somewhat confusingly, in English. (He later introduces himself as a former New Hampshire state legislator, so he’s pretty clearly not a local. It doesn’t seem like he has much experience running meetings where English proficiency is an issue.)

At 53:34, someone from the floor shouts out: “Excuse me, chair? Some people don’t speak English. Can we have a Spanish translator with you?” There’s a pause, and she says again, “Spanish?”

He replies, “It doesn’t say anything yes or no, but sure. Who is a Spanish speaker?” At this point, crosstalk begins. It sounds like someone says “Dolores.” Someone else says, “The lady by the mic right there.” As the murmuring of the crowd intensifies, he says, “Can we do it quickly?” Then he says, “First person on the stage who speaks Spanish gets to do it. Climb up the stage, then.”

At this point, at about 54:08, people start getting angry, and rightly so. Rather than check on procedure, try to find a neutral translator, or pause the proceedings so that the two sides can come up with a joint plan, the chair is abdicating his responsibility to oversee the process, allowing whoever rushes the stage first to take a major role in the running of the vote. People start shouting “No!” and jeering him. Apparently referring to Huerta, someone yells out “She’s a surrogate!” Near the video mic, you hear someone say tensely, “You have to get up there now.” (On another video of the confrontation, you can hear someone shouting “Neutral! Neutral!” at this point.)

At about 54:30 the chair tries to calm things down, clearly still winging it. “Okay. Okay. Shh. Shh. Okay. Shh. She’s not gonna … Okay. We’ve already got one person. Hold on. Hold on. Hold on everybody. I’m gonna have to clear the back if you keep shouting. You are observers, not cat-callers.”

Responding to the objections, the chair notes that there are a lot of Spanish-speakers in the room, and suggests that “Anything that she says, you’re going to be able to see if she says anything that’s pro-Hillary, right?” Someone shouts “Absolutely not.” Someone else says, “Come on. This is the wrong time.” There’s more crosstalk, and someone says something to him on the stage. At that point, at about 55:20, the chair gives up, and says “We’re moving forward in English only.” There’s a few seconds of clapping, and a few seconds of confusion, and then they start the vote.

The whole thing, from start to finish, lasted a little over two minutes.

I wasn’t in the room, so I may be missing some details, but what happened seems pretty straightforward. Someone asked for a translator. The chair agreed without thinking it through or coming up with a sensible plan. Huerta stepped up to serve, and others objected. The chair tried to answer the objections, realized he wasn’t getting anywhere, and reversed himself — using a phrase (“English only”) that a more culturally proficient moderator would have known to avoid. People on both sides got their noses out of joint as a result of his ham-handedness, but the caucus continued with no major disruption.

So why were the initial reports of the incident so at odds with what the video shows?

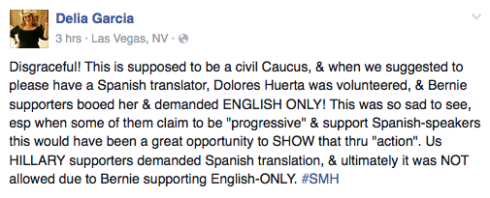

Some people — a lot of people, if my Twitter mentions from last night are anything to go by — see an intentional smear, a lie spread maliciously by the Clinton camp. But I’m not so sure. Let’s look at where the story started, with a Facebook post from Clinton supporter Delia Garcia:

If you parse this description closely, it’s actually pretty accurate. The Clinton camp did ask for a translator. Huerta did volunteer. Sanders supporters did object, and did boo — though they may have been booing the chair, or the attempt to put Huerta on stage, that’s a pretty slender distinction. The chair did reject Spanish translation, using the phrase “English only,” and the Sanders camp did seem to support his decision. The claim that Sanders people “demanded ENGLISH ONLY” isn’t confirmed by the video, but it’s possible that happened too — that someone said it wasn’t practical to have translation, so the caucus should go forward in English.

This is a partisan reading of the dispute, and it’s got quite a bit of editorializing that Sanders supporters can rightly object to, but as a factual account it’s somewhere between mostly and completely supported by the video.

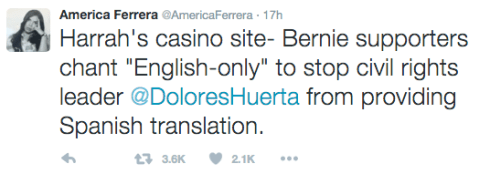

The next big step in propagating the story was a tweet from actress America Ferrera:

It’s not clear whether Ferrera was at the caucus, but if she wasn’t — or if she didn’t see and hear the incident clearly — this tweet can be read as a summary of Delia Garcia’s Facebook post. It’s a bit garbled, and a bit more heated, but if Ferrera was working from Garcia’s post, her tweet seems more of a hyperbolic gloss than a straight-up lie.

The one big apparent error in Ferrera’s tweet is the use of the word “chant.” It seems pretty clear from the video that there was no such chant at any point, and it looks like the phrase “English only” was introduced by the chair after the decision was made. It’s possible that the video missed something, and that someone in Sanders’ camp did use the phrase, but my (maybe too charitable) guess is that Ferrera got it from Garcia and wrongly inferred quotation marks from Garcia’s account.

And the most damaging part of Ferrera’s tweet isn’t even the part that’s apparently wrong. Taken in isolation, the claim that Sanders supporters yelled “to stop [Huerta] from providing Spanish translation” suggests that Huerta was shouted down — that she was performing a service to Spanish-speaking caucusgoers, and was chased from the stage by racists. It’s clear that that didn’t happen.

But that interpretation of the tweet — and it was my interpretation, when I read it — isn’t actually in the text. It’s true that Huerta was prevented from serving as a translator by vocal objections from Sanders supporters, and watching the video, I’m fine with that happening. It was my inferences, not her claims — aside, again, from the use of the word “chant” — that were wrong.

Later, Huerta retweeted Ferrera and supplied a tweet of her own:

To the “chanting” allegation, Huerta adds the claim that she was “silenced.” That’s an incendiary charge, and in the context of what a lot of us were assuming happened, it reinforces the idea that she was shouted down. But Huerta doesn’t actually say that she was shouted down — in fact, none of these three accounts make that claim.

And that’s what’s most interesting to me about all this, both as a historian who often works with first-person accounts of contentious events and as a guy who lives on the internet. None of these women are clearly lying. Most of what they say is accurate, and it’s possible they all believe they’re telling the whole truth. But the impression that they collectively left was wildly misleading.

People don’t need to be evil to get these stories wrong. They don’t even need to lie. They just need to speak imprecisely, as we all do, and use hyperbolic language, as we all do. You don’t need a conspiracy to spread these stories — it turns out that a game of Telephone works just as well in text-based media as it does when you’re whispering in the dark.

So I don’t blame Garcia or Ferrera or Huerta all that much for saying what they did last night. They seem to have gotten the story wrong — more so with each iteration — but I’m happy to accept that they may have been mistaken and imprecise, not intentionally misleading. If I’m right about that, they should correct the record today.

The real takeaway is this: Stories get garbled. Stories get exaggerated. We should read skeptically, particularly when what we’re reading backs up what we think we already know. Skepticism is good. It’s not wrong to put the brakes on something like this while you gather facts, and it’s not wrong to say that the people sharing their accounts could be mistaken. Even if they were there. Even if they’re Dolores Huerta.

But if you’re media? If you’re media and you run with a story like this without doing your job and finding out what happened? If you’re media and you don’t understand how all this stuff works?

Well, then you’re the problem.

Update | In an interview after the caucus, Huerta said this (video begins in the middle of her statement): “…shouting, ‘No, no, no.’ And so then a Bernie person stood up and said, ‘no, we need to have … I can also do translation,’ whatever. So anyway, then the person running the caucus said, ‘well, we won’t have a translator.’ But the sad thing about this is that some of the [Sanders] organizers were shouting ‘English only, English only.'”

Recent Comments